Norwood, Bendavis and Cabool, Missouri

Posted by graywacke on June 28, 2021

First timer? In this formerly once-a-day blog (and now pretty much a once-a-week blog), I use an app that provides a random latitude and longitude that puts me somewhere in the continental United States (the lower 48). I call this “landing.”

I keep track of the watersheds I land in, as well as the town or towns I land near. I do some internet research to hopefully find something of interest about my landing location.

To find out more about A Landing A Day (like who “Dan” is) please see “About Landing” above. To check out some relatively recent changes in how I do things, check out “About Landing (Revisited).”

Landing number 2529; A Landing A Day blog post number 973

Dan: Today’s lat/long (N37o 15.924’, W92o 15.470) puts me in south central Missouri:

And my local landing map:

I’ll head over to Google Earth (GE) to get a look at my local watershed:

As you can see, I landed in the watershed of the North Fork of Beaver Creek, which of course is part of the Beaver Creek watershed. Moving to StreetAtlas:

Beaver Creek finds itself to be part of the Gasconade River watershed (3rd hit); which in turn is but a small portion of the much larger Missouri River watershed (446th hit). And speaking of much larger watersheds, this all leads to the fourth largest watershed in the world – the Mighty Mississippi.

For those who care, the Amazon basin is the largest, followed by the Congo and the Nile. From a length perspective the Amazon and Nile are nip and tuck, followed by the Yangtze and then the Mississippi/Missouri.

The OD was shut out while seeking a peek at the North Fork of Beaver Creek, but he did get a look at the Beav:

And here’s what he sees:

You can see by see by the dearth of blue lines on the above GE map, the OD can’t get anywhere close to my landing. Oh, well.

I’ll first take a quick look at Norwood. From Wiki:

Norwood was laid out in 1882. The community’s name was inspired by the novel “Norwood: or, Village Life in New England,” by Henry Ward Beecher.

Henry Ward was wiki-clickable:

Henry Ward Beecher (1813 – 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God’s love, and his 1875 adultery trial.

Several of his brothers and sisters became well-known educators and activists, most notably Harriet Beecher Stowe, who achieved worldwide fame with her abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

About “Norwood:”

In 1865, Robert Bonner of the New York Ledger offered Beecher twenty-four thousand dollars to follow his sister’s example and compose a novel.

AYKM? A $24,000 advance? In today’s dollars, it’s about $450,000!

The subsequent novel, Norwood, or Village Life in New England, was published in 1868. Beecher stated that his intent for the book was to present a heroine who is “large of soul, a child of nature, and, although a Christian, yet in childlike sympathy with the truths of God in the natural world, instead of books.”

McDougall describes the resulting novel as “a New England romance of flowers and bosomy sighs … ‘new theology’ that amounted to warmed-over Emerson”. The novel was moderately well received by critics of the day.

There you have it. Well, someone from 19th-century Missouri evidently thought it was a great book. . . .

Here’s another quick-hitter: Bendavis. Funny thing, just a couple of posts ago, I wrote about Ben Lomond, Arkansas. I wondered if the town were named after a guy named Ben Lomond. Turns out that Ben Lomond is a Scottish mountain on the shores of Loch Lomond.

So here I am at Bendavis. Ben Davis? Was there an early settler or railroad executive named Ben Davis? Once again, the answer is no. Wiki tells us that the town was named after the Ben Davis variety of apple, which was wiki-clickable:

During the 19th century and early 20th century, it was a popular commercial apple due to the ruggedness and keeping qualities of the fruit. However, as packing and transportation techniques improved the Ben Davis fell out of favor, replaced by others considered to have better flavor.

It was known to fruit growers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a “mortgage lifter” because it was a reliable producer and the fruit would not drop from the trees until very late in the season. By mid-twentieth century it was mostly used as a process apple rather than a table apple, and orchards were replacing it with more popular varieties. The Ben Davis is now very rare to nonexistent in the commercial trade.

Moving on to Cabool. Cabool is named after Kabul, Afghanistan, and it turns out that I featured Cabool AR (and therefore Kabul) some years back – almost exactly six years back to be more precise. I checked out my post and really liked it. So rather than just referencing it I’m going to present a big chunk of it in full. Here goes. Until otherwise noted, all that follows is from that post:

Right away I found out (no surprise here) that Kabul does not have Google Street View.

But Panarmio photos? It’s loaded. Here’s just a part of the city, showing Panaramio locations (the blue dots).

[Note from today: There’s still no Street View. The Orange Dude couldn’t get a visa . . .]

Some of the larger blue dots have dozens and dozens of photos. Amazingly, the first one I randomly looked at was this (by aka4ajax) of a little boy and an ice cream vendor:

I love this photo . . .

Now let’s look at some city overviews with mountains in the background. First this, by Eng Raqib Safari:

And this, by Quique Morrique (great name!):

And, yes, they have traffic jams (by Nasim Fedrat):

And here’s the Abdul Rahman mosque (one of Kabul’s finest), by (once again), Eng Raqib Safari:

There are four ancient forts in Kabul (that I stumbled on by looking at GE). I can’t find anything much about any of them, except that the oldest (I think) is Bala Hissar, which was built in the 5th century A.D. Here’s a shot looking up at Bala Hissar by Ahmad Shah Nas:

And here are some scars of war at Bala Hissar (by Jack Kranz):

Bala Hissar is outside of center city, but right in town are three forts:

I found some pictures of the various forts. I’ll start with this, by naw448:

And this by (once again by the photographer of boy & and ice cream vendor, aka4ajax):

And this by Azanizinaza:

Also by Azanizinaza, lingering evidence of war:

I couldn’t really find much in the way of information about any of the forts, but it’s sad, really, that historic sites that would be major tourist attractions (and a source of local pride) in most places around the world end up being an afterthought in war torn Afghanistan.

After looking at dozens of Panoramio shot, I kept two more. First this one of a traditional mud house (by Golam Kamal):

And then this great street scene (Potter’s Row?) by Ahmad Azizyar:

My mind wandered around Afghanistan (in a very limited way, considering my very limited knowledge of Afghanistan), and settled on the Khyber Pass, which is located a little more than a hundred miles east of Kabul, on the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. From Wiki:

The Khyber Pass (elevation 3,510 ft) is a mountain pass connecting Afghanistan and Pakistan, cutting through the northeastern part of the Spin Ghar mountains. An integral part of the ancient Silk Road, it is one of the oldest known passes in the world. Throughout history it has been an important trade route between Central Asia and South Asia and a strategic military location.

Here’s a Wiki photo of the pass (from the Afghan side) by James Mollison:

I know I need a map showing Khyber Pass, but I’ll do it via the Silk Road. Here’s a Nat Geo Silk road map:

I found an Afghan-centric write-up about the Silk Road from the Queensland (Australia) Museum site (they were featuring Afghan artifacts in a 2014 exhibit):

The Silk Road was not a single “road”, but rather a network of trade routes that linked cities, trading posts, hostels and caravan-watering places. It was most active from about 300 BC to 200 AD and extended between the Eastern Roman frontier in the Middle East to the Chinese frontier, with other paths going north through Afghanistan from the Indian Ocean to the Siberian Steppe.

Products were seldom carried from one end of the Silk Road to the other by the same merchants. People in these widely separated locations participated in the trade network by adding various goods to the caravans as they passed through markets along the way: ivories from India, horses from Siberia and Mongolia, rubies and garnets from Afghanistan, and carpets from Persia and northern Central Asia.

A little further down in the Wiki Khyber Pass write-up was this innocuous little sentence:

The Pass became widely known to thousands of Westerners and Japanese who traveled it in the days of the Hippie Trail, taking a bus or car from Kabul to Peshwar, Pakistan on their way to mainly India and/or Nepal.

As a child of the 60s, I was aware of many Hippie-types traveling to seek out gurus back in the day (like the Beatles). But I never would have guessed that “Hippie Trail” had its own Wiki site:

The hippie trail (also the Overland) is the name given to the journey taken by members of the hippie subculture and others from the late 1950s to the 1970s from Europe, overland to and from southern Asia, mainly India and Nepal.

The hippie trail was a form of alternative tourism, and one of the key elements was travelling as cheaply as possible, mainly to extend the length of time away from home.

In every major stop of the hippie trail, there were hotels, restaurants and cafés that catered almost exclusively to cannabis-smoking Westerners, who networked with each other as they travelled east and west. The hippies tended to spend more time interacting with the local population than traditional sightseeing tourists.

Here’s a Wiki map of the trail (by Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons):

Continuing:

Hippies tended to travel light, seeking to pick up and go wherever the action was at any time. Hippies did not worry about money, hotel reservations or other such standard travel planning. A derivative of this style of travel were the hippie trucks and buses, hand-crafted mobile houses built on a truck or bus chassis to facilitate a nomadic lifestyle.Some of these mobile homes were quite elaborate, with beds, toilets, showers and cooking facilities.

The hippie trail came to an end in the late 1970s with political changes in previously hospitable countries. In 1979, both the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan closed the overland route to Western travelers.

Here’s a great Hippie Trail shot, from RumRoadRavings.com:

[Just think! Today, this is a bunch of Boomers like me . . .]

Here’s another (this one a “oh-oh” moment), from a blog post entitled “The Hippie Trail – The Road to Paradise” (reminisces about the author’s Hippie Trail adventure, with the caption below):

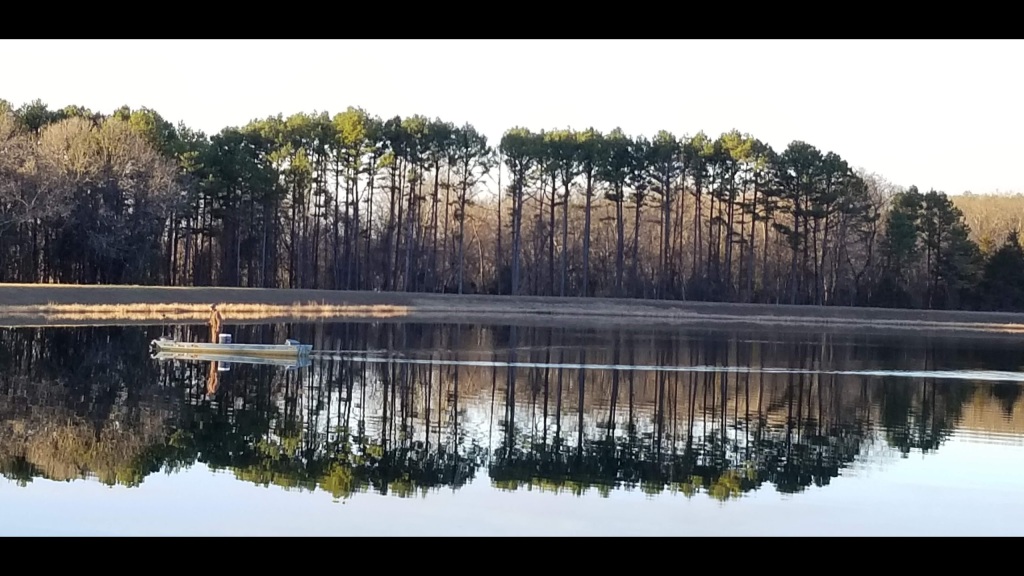

Back to now: I’ll close with this great shot of Austin Lake (about 8 miles SSE of my landing) by PartyPals Mom:

That’ll do it . . .

KS

Greg

© 2021 A Landing A Day

Leave a comment